Four commitments unlock financing for the full district.

| Key | Requirement | What It Proves |

|---|---|---|

| Land | Site control | Traditional authority is committed |

| University | Letter of interest | Academic anchor is secured |

| Hospital | Letter of interest | Medical anchor is secured |

| Contractor | International builder | Execution capability exists |

With all four keys, financing parties see: site is secured, institutions are committed, execution capability is proven. The gate opens.

Behind the Gate

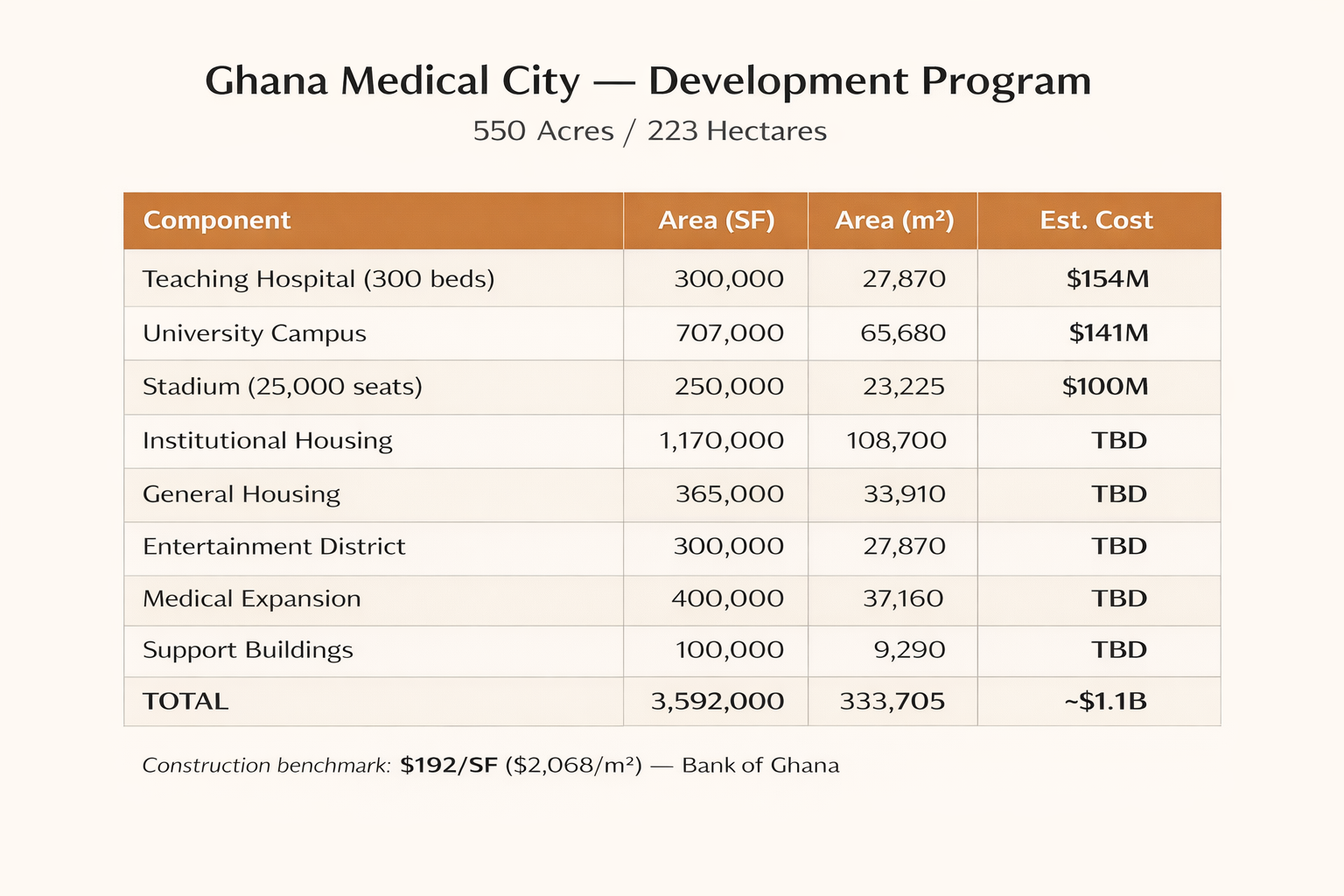

The Development District: teaching hospital, university campus, covered stadium, entertainment district, housing. $1.1 billion total program. Phase 1 (hospital + university) unlocks everything that follows.

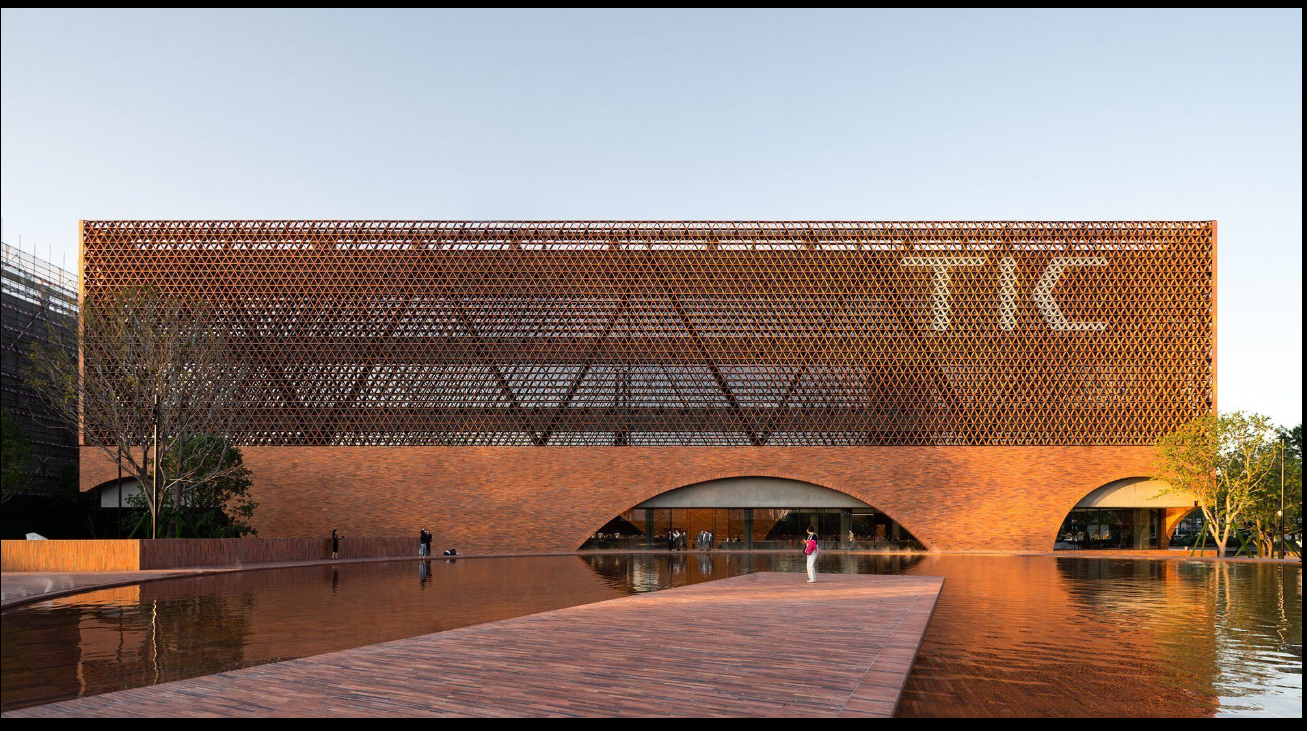

Climate-Responsive Design

Ghana per capita income: $2,400/year. HVAC runs 40-70% of hospital operating budgets in tropical climates. Glass curtain wall buildings require constant air conditioning. Glass achieves R-4.3 insulation; masonry and earth construction achieves R-50.

The difference determines whether facilities can operate sustainably on local revenue.

Institutional Visual Language

Ghana's respected institutions share common architectural elements: white walls, red clay tile roofs, towers, covered walkways, formal quadrangles. University of Ghana (Legon), Achimota School, Korle-Bu Hospital — this is what a serious institution looks like to Ghana's decision-makers.

They walked through these spaces for years. The visual vocabulary is encoded. A building that speaks this language communicates permanence, legitimacy, belonging.

Land in Ghana operates under traditional authority. The pathway to site control follows established protocol.

| Role | Function |

|---|---|

| Development Ambassador | Introduces project, maintains relationship, coordinates communication |

| Apedwahene (Chief of Apedwa) | Divisional chief, guards pathway to royal capital, affirms local support |

| Okyenhene (King of Akyem Abuakwa) | Holds allodial title, signs the land, final approval authority |

The Apedwahene has publicly stated: "All land transactions in Apedwa must first seek consent of the chief. Final and decisive approval must come from the Okyenhene."

Site Details

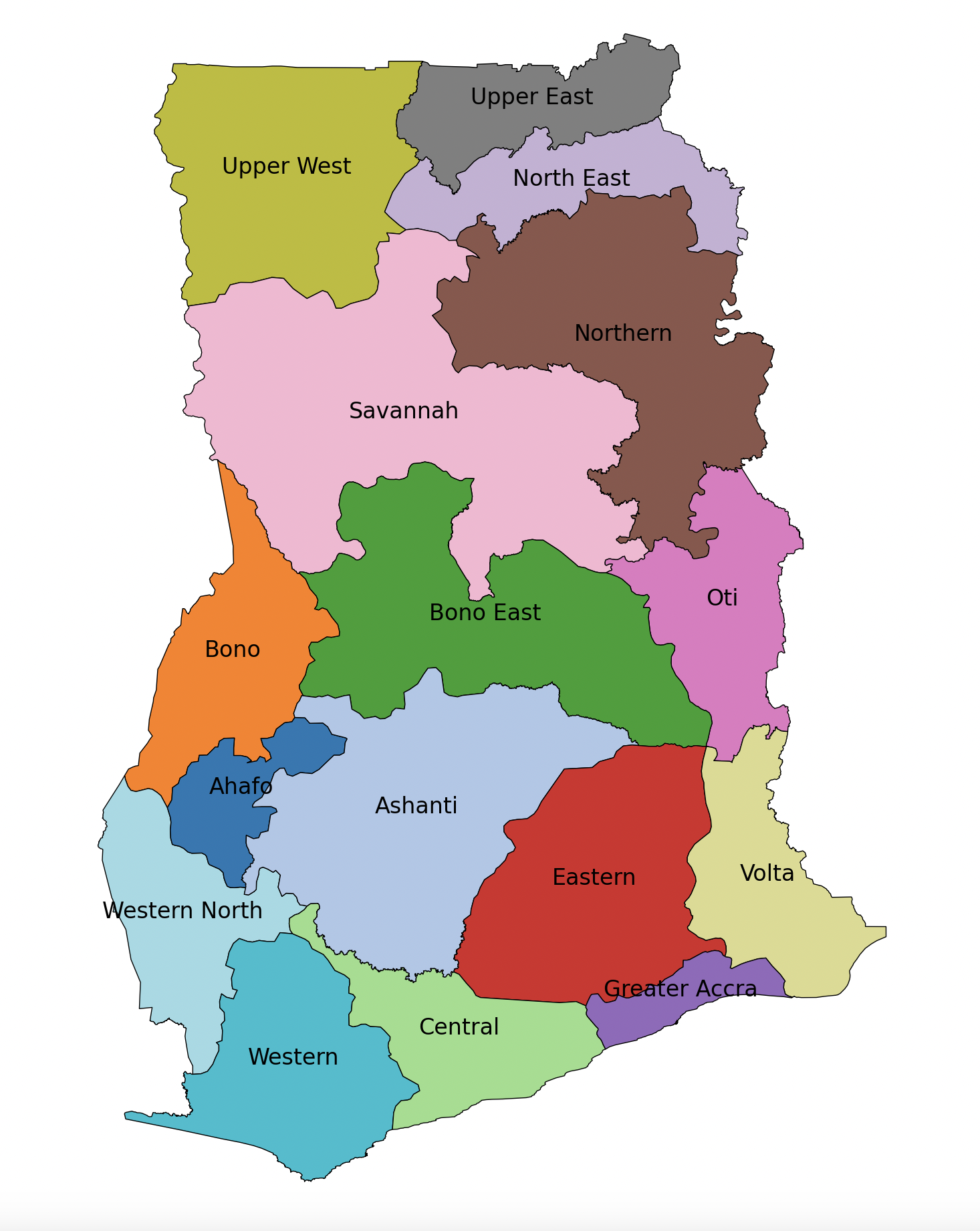

550 acres demarcated in Akyem Apedwa, Eastern Region. Population served: 2.9 million without tertiary healthcare access. Distance from Accra: approximately 90 kilometers via the Accra-Kumasi corridor.

Ready, Willing, and Able letter on file. Customary affirmation initiates formal documentation process.

Ghana's tertiary enrollment rate: 22%. Global average: 40%. The gap is 18 percentage points.

At University of Ghana, acceptance rate is approximately 18%. Many qualified students cannot be admitted due to limited spaces.

| Component | Area (m²) | Area (SF) |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Buildings | 13,300 | 143,160 |

| Student Housing | 11,400 | 122,710 |

| Support Facilities | 9,300 | 100,100 |

| Athletic Facilities | 27,000 | 290,630 |

| Infrastructure | 7,200 | 77,500 |

| Total | 68,200 | 734,100 |

Ghana's public universities have cash flows directed to the Treasury Single Account. They cannot control their own revenue. A lease commitment backed by government budget allocation is not bankable given Ghana's credit situation (CCC+).

The solution: An affiliate structure — a separate legal entity sponsored by an existing chartered university.

| Entity | Role |

|---|---|

| Chartered University | Provides accreditation, academic oversight |

| Affiliate Entity | Signs the lease, controls its own revenue |

| Revenue Sources | Tuition, clinical fees, research grants |

Cash flows stay in the affiliate entity, not subverted to Treasury. Ghana already has 21 institutions affiliated with University of Ghana. This is a known structure.

| Party | Benefits |

|---|---|

| University | Expansion without capital risk, teaching hospital integration, grant eligibility |

| Ghana | Hospital and university built with zero sovereign debt, eventual ownership |

| Developer/Investor | Lease signed by entity with predictable revenue streams |

White walls, red clay tile roofs, clock tower, formal quadrangle, covered walkways, mature trees.

Ghana's elite were formed by Methodist and Presbyterian mission schools — Achimota, Mfantsipim, Wesley Girls. Their visual vocabulary was built in these institutions.

| Institution | Visual Elements |

|---|---|

| Korle-Bu Hospital (1923) | Colonial institutional template |

| Achimota School | Red clay tiles, white walls, formal quadrangles |

| University of Ghana, Legon | Gable roofs, red tiles, tropical compound buildings |

These buildings encode a message: institution, permanence, learning, safety.

Ghana's decision-makers have the codes to decode that message. A building that speaks this language communicates legitimacy.

The Gap

The Eastern Region: 2.9 million people, zero tertiary teaching hospitals.

In Ghana's rural regions, 54% of maternal deaths occur within 24 hours of hospital admission. Many women travel 150 kilometers or more from clinics without blood supplies, surgical capacity, or specialist staff.

Ghana has 1.4 physicians per 10,000 population. Germany has 45.

Program Scale

300-bed teaching hospital: 300,000 SF / 27,870 m². Tertiary care, surgical suites, medical imaging, ICU, teaching facilities.

What a Letter of Interest Demonstrates

A hospital letter of interest from a qualified operator demonstrates healthcare demand and provides the medical anchor for the district. The operator's commitment — backed by their balance sheet and operating revenue — is what makes the lease bankable.

Target Operator Profile

Healthcare systems with Africa experience, institutional credit (balance sheet strength to support lease or operating agreement), teaching hospital capability, and medical tourism experience.

Courtyards, covered walkways, brise-soleil screens, passive ventilation, brick and masonry construction, deep overhangs.

The Economics

Ghana per capita income: $2,400/year ($193/month). HVAC runs 40-70% of hospital operating budgets in tropical climates. Dehumidification alone accounts for 80%+ of ventilation energy.

Glass curtain wall achieves R-4.3 insulation value. Masonry and earth construction achieves R-50. The difference determines whether a facility can operate sustainably on local revenue.

Proven Approaches

Climate-responsive hospital design has been validated across tropical climates. For example:

JCI-accredited facilities in East Africa featuring ceramic brise-soleil, open-air verandas, courtyard microclimates, and cross-ventilation. The upper floors are veiled with custom ceramic block screens that provide patient privacy and filter the tropical sun. A veranda concourse connects buildings externally — circulation that works with the climate rather than sealing against it.

Surgical clinics in West Africa using rammed earth and passive ventilation only — no air conditioning — serving 50,000 people in regions where temperatures regularly exceed 37°C.

Research from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology documents 48-50% energy reduction with passive strategies in Ghana's climate zones.

Audience Alignment

The Okyenhene (King of Akyem Abuakwa) founded the Okyeman Environment Foundation. He has destooled chiefs for illegal mining. He serves as Honorary Vice President of BirdLife International and speaks internationally on environmental stewardship.

Climate-responsive architecture — a building that works with the land rather than against it — speaks his language.

Site: 550 Acres / 223 Hectares

Total Building Program: 3,592,000 SF / 333,705 m²

| Component | Area (SF) | Area (m²) |

|---|---|---|

| Teaching Hospital (300 beds) | 300,000 | 27,870 |

| University Campus | 734,000 | 68,200 |

| Stadium (25,000 seats) | 250,000 | 23,225 |

| Institutional Housing | 1,170,000 | 108,700 |

| General Housing | 365,000 | 33,910 |

| Entertainment District | 300,000 | 27,870 |

| Medical Expansion | 400,000 | 37,160 |

| Support Buildings | 100,000 | 9,290 |

A project of this scale requires an international contractor with demonstrated capacity.

Interest from a qualified builder signals the project can be executed.

Turkish construction firms have completed $85 billion in projects across Africa. They constitute 40 of the world's 250 biggest international contractors.

Built airports, convention centers, parliament buildings, railways, hospitals, and commercial complexes across the continent.

A builder relationship confirms execution capability to financing parties.

Ghana's credit rating (CCC+) makes traditional government-backed PPPs unbankable. International capital markets apply risk premiums to emerging market sovereign obligations.

This structure bypasses sovereign credit entirely. Institutional tenants — the university and healthcare operator — provide the credit foundation.

| Role | Entity | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Landlord | Ghana | Provides land, receives lease payments, owns asset |

| Tenant | Institutional partner | Signs lease, pays rent, operates facility |

| Credit Source | Operator's balance sheet | Corporate credit supports construction financing |

Land (through traditional authority), regulatory pathway, demand (2.9 million unserved population).

Ghana contributes no capital. Ghana assumes no debt obligation.

Lease payments, franchise fees, jobs, tax revenue, infrastructure — and ownership of all improvements at end of lease term.

Zero sovereign debt obligation.

Construction financing carries costs reflecting development risk. Stabilized assets with creditworthy tenants trade at lower capitalization rates.

The spread between construction cost and stabilized value is developer profit — compensation for execution risk.

For every $1 million of annual rent:

| Stage | Cap Rate | Asset Value |

|---|---|---|

| Construction (development risk) | 8% | $12.5 million |

| Stabilized (institutional tenant) | 6% | $16.7 million |

| Value Creation | $4.2 million |

The 2% spread creates approximately 33% value gain. This ratio scales with project size.

A creditworthy tenant transforms speculative construction into an investment-grade asset.

Pension funds, insurance companies, and REITs seek stable returns. They accept lower yields for predictable income backed by institutional credit. That willingness to accept 6% instead of 8% is what creates the value spread.

Akan Adinkra symbol meaning "sack of cola nuts." Represents affluence, abundance, and prosperity through unity.

"Sika yɛ mogya" — "Money is like blood." Wealth supports the well-being of the community.

The hospital and university are the core engine. Once running, everything else becomes possible.

| Phase | Components |

|---|---|

| 1 | Hospital + University (anchor facilities) |

| 2 | Stadium + Entertainment District |

| 3 | Housing + Expansion |

1. Overview

An introduction to the Ghana Medical City development, its location, and the opportunity it represents for healthcare, education, and economic development in the Eastern Region.

Ghana Medical City proposes a 300-bed teaching hospital, a university campus with capacity for 5,000 to 6,000 students, a stadium, and supporting amenities in the Eastern Region.

In Ghana's rural regions, 54% of maternal deaths occur within 24 hours of hospital admission. Many women are transported 150 kilometres or more from clinics without blood supplies, surgical capacity, or specialist staff. Ghana has 1.4 physicians per 10,000 population. Germany has 45.

Public universities in Ghana face an overwhelming influx of students seeking admission, surpassing their capacity. At University of Ghana, the Pro Vice-Chancellor has stated: "Every year, we have many more students making the cut off but not getting the opportunity to be admitted because of the limited number of spaces." The university's acceptance rate is approximately 18%.

References: WHO Global Health Observatory; Ghana MOH Maternal Health Survey; Prof. Gordon Awandare, UG Pro Vice-Chancellor, Citi News December 2025; EduRank/National Accreditation Board.

The development addresses documented gaps while creating returns for participants.

The Eastern Region gains its first tertiary teaching hospital. University capacity expands. Infrastructure is developed without sovereign debt obligation.

| Healthcare | Tertiary hospital serving 2.9 million residents currently without such access |

| Education | University places in a system where enrollment falls 18 percentage points below global average |

| Employment | Construction phase positions, permanent operational roles |

| Economic Activity | $280+ million Phase 1 spending, ongoing operational expenditure |

| Fiscal Burden | None—no government funding required |

| University Partner | Purpose-built campus, teaching hospital affiliation, grant eligibility ($55-280M potential), faculty pipeline |

| Healthcare Operator | Anchor position in underserved region, teaching hospital status, medical tourism infrastructure |

| Stadium Operator | Covered venue (West Africa's first), integrated entertainment district, anchor tenant traffic |

| Hotel Operators | Multiple demand drivers (hospital, university, stadium, events), limited regional competition |

The traditional authority and people of Akyem Apedwa receive consideration for land access while retaining underlying ownership through a term lease structure.

| Customary Fees | Appropriate payments through proper channels |

| Employment Priority | Construction and operational positions for local residents |

| Healthcare Access | Tertiary hospital within the community |

| Economic Activity | Wages and purchasing circulating in local economy |

| Land Retention | Term lease preserves traditional ownership; improvements transfer at conclusion |

The proposed development comprises 553 acres in Akyem Apedwa, Eastern Region, Ghana. The full district represents an investment of approximately $1.1 billion across six integrated components.

| Component | Scale | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Tertiary Teaching Hospital | 300 beds | $120-140 million |

| Teaching University | 68,200 m² | $141 million |

| Covered Stadium | 25,000 seats | $100 million |

| Entertainment District | 35 acres | To be determined |

| Housing Districts | Multiple phases | To be determined |

| Infrastructure | District-wide | To be determined |

Each component maintains financial independence while sharing operational interconnections with the others.

A hospital operating in isolation faces considerable challenges. A stadium without supporting services captures limited revenue. However, a hospital situated within a university district, adjacent to a stadium with entertainment and housing facilities, functions as an integrated urban centre with diversified revenue streams and mutual reinforcement among its components.

| Hospital + University | Teaching hospital affiliation, medical education, clinical research |

| Stadium + Entertainment | Event attendance generates hotel, restaurant, retail demand |

| University + Housing | Student accommodation, faculty residences, workforce retention |

| Hospital + Entertainment | Medical tourism patients require hotels, restaurants during recovery |

| All Components | Shared infrastructure reduces per-component costs |

Facilities operating in isolation compete for resources. Integrated districts share them.

Central Park, comprising 5 to 10 acres, will anchor the entertainment district. The park will provide landscaped green space with a 2,000-seat amphitheater.

Urban planning research consistently demonstrates that people require gathering places and green areas. This principle has been validated across diverse contexts.

The entire district will be designed for walkability. All amenities will be accessible within a ten-minute walk. The scale will be intimate rather than sprawling—similar to successful entertainment districts that prioritize pedestrian experience over vehicular circulation.

Three significant infrastructure gaps converge in this single project.

The Eastern Region of Ghana recorded a population of 2,925,653 in the 2021 Population and Housing Census conducted by the Ghana Statistical Service. At present, the region has no tertiary teaching hospital.

Ghana maintains five public teaching hospitals. None of these serves the Eastern Region directly.

| Teaching Hospital | Location | Region Served |

|---|---|---|

| Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital | Accra | Greater Accra |

| Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital | Kumasi | Ashanti |

| Tamale Teaching Hospital | Tamale | Northern |

| Cape Coast Teaching Hospital | Cape Coast | Central |

| Ho Teaching Hospital | Ho | Volta |

| Eastern Region | None | 2.9 million unserved |

The Eastern Region Hospital in Koforidua provides regional-level services but does not offer tertiary teaching hospital capabilities. For emergencies requiring tertiary intervention—trauma, stroke, cardiac events, complicated births—residents must travel to Accra or Kumasi. Travel time affects outcomes.

A regional hospital project is under construction in Koforidua with 285 beds, financed through UK Export Finance. This facility will enhance regional capacity but will not provide teaching hospital status or the full range of tertiary services.

Ghana's tertiary school enrollment rate stood at 21.99 percent in 2023, according to World Bank data. The global average is 40.35 percent. Ghana falls significantly below the international benchmark.

| Ghana Tertiary Enrollment | 21.99% (2023) |

| World Average | 40.35% |

| Gap | 18.36 percentage points |

| Total Tertiary Students | 635,000 (2022) |

| Accredited Institutions | 310 |

Each year, qualified students are unable to secure places at universities due to capacity constraints. Public university places remain limited relative to demand. Private institutions seeking to operate must affiliate with a chartered public university before obtaining independent presidential charter.

Students from families with sufficient means pursue their education abroad. In 2021, approximately 20,300 Ghanaian tertiary students were studying in other countries.

The Eastern Region presents specific characteristics relevant to this development.

| Population | 2,925,653 (2021 Census) |

| Land Area | 19,323 square kilometres |

| Share of Ghana | 8.1% of national land area |

| Urban Population | 51.5% (2021) |

| Regional Capital | Koforidua |

| Growth Rate | 1.0% annually (lowest among regions) |

The low population growth rate reflects net out-migration from the region. Improved infrastructure and economic opportunity may address this pattern.

- Ghana Statistical Service. "2021 Population and Housing Census: General Report Volume 3A - Population of Regions and Districts." statsghana.gov.gh (Accessed December 2025)

- Ghana Ministry of Health. "Teaching Hospitals." moh.gov.gh (Accessed December 2025)

- World Bank. "School enrollment, tertiary (% gross) - Ghana." data.worldbank.org (Accessed December 2025)

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. "Number of students enrolled in tertiary education in Ghana." Via Statista. (Accessed December 2025)

- Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. Official website. kbth.gov.gh (Accessed December 2025)

- Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. Official website. kath.gov.gh (Accessed December 2025)

Phase 1 comprises two anchor facilities. These represent two separate transactions.

| Component | Estimated Cost | Credit Source |

|---|---|---|

| University Campus | $141 million | International university institutional credit |

| Teaching Hospital | $120-140 million | Healthcare operator corporate credit |

| Shared Infrastructure | $20-30 million | Allocated across anchor facilities |

| Phase 1 Total | $280-310 million |

The university and hospital maintain interdependence. A teaching hospital requires university affiliation. A medical school requires a teaching hospital. Together these facilities create critical mass.

Both facilities can be financed through lease-backed structures with creditworthy institutional tenants. Neither requires reliance on Ghana sovereign credit.

The stadium, entertainment district, and housing will follow once the anchor facilities are established and operational.

The university partner will sign a lease for the campus. The university's institutional credit will support the obligation.

The healthcare operator will sign a lease for the hospital. The operator's corporate credit will support the obligation.

The facilities share a site. Operations will be integrated. Financing remains separate.

| University Transaction | Long-term lease, parent institution guarantee |

| Hospital Transaction | Operating agreement or lease, corporate credit backing |

| Shared Elements | Site, infrastructure, teaching hospital affiliation |

| Separate Elements | Financing, operations, revenue streams |

This document serves multiple audiences. Each may find certain sections more relevant than others.

| If You Are | Focus On |

|---|---|

| Traditional Authority | Overview, Components, Key Questions → Land Pathway |

| University Partner | Overview, Components → University, Grants, Key Questions → University Partners |

| Healthcare Operator | Overview, Components → Hospital, Key Questions → Healthcare Operators |

| Stadium or Hotel Operator | Overview, Components → Entertainment District, Key Questions → Entertainment & Hospitality |

| Pre-development Funder | Overview, Structure, Key Questions → Pre-development Funders |

| Government Official | Overview, Structure → Benefits to Ghana, Key Questions → Logic of This Structure |

The accordion structure allows readers to expand sections of interest while bypassing material less relevant to their purpose. No audience is expected to review every section in detail.

The Key Questions section addresses typical concerns raised by each stakeholder category. These sections anticipate and respond to objections that prospective partners commonly raise.

This document employs formal English consistent with Ghanaian professional communication standards.

Ghanaian business culture values deliberate, measured expression. Hierarchy and respect for institutions shape communication norms throughout West Africa. The directness common in American business writing may be perceived differently in this context.

The formal register reflects the document's intended audience and purpose. Readers from the United States may notice a more measured tone than typical American business communications. This is intentional.

| Register | Formal Ghanaian English |

| Contractions | Not employed (cannot, do not, will not) |

| Sentence Structure | Complete sentences throughout |

| Connectives | Formal (Furthermore, Moreover, In addition) |

| Tone | Observational, measured, respectful of institutions |

The communication style aligns with standards observed in Ghana's leading publications and professional correspondence. This approach facilitates engagement with traditional authorities, government officials, and institutional partners within Ghana.

2. Components

The six integrated components that comprise the Ghana Medical City district, each designed to support and enhance the others.

The hospital will comprise 300 beds at tertiary teaching level, providing the Eastern Region's first such facility.

| Component | Specification | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|

| General Patient Wards | 270 beds | $27 million |

| Intensive Care Unit | 30 beds, including TBI rehabilitation | $7.5 million |

| Operating Theatres | 6 surgical suites | $18 million |

| Medical Imaging | CT, MRI, X-ray, ultrasound | $8 million |

| Laboratory Facilities | Clinical and pathology services | $4 million |

| Mechanical and Electrical | HVAC, power systems, backup generation | $25 million |

| Teaching Facilities | Classrooms, simulation laboratories | $5 million |

| Site Infrastructure | Roads, utilities, helipad | $6 million |

| Subtotal | $100.5 million | |

| Contingency and Soft Costs | $17-40 million | |

| Total | $117-140 million |

The cost basis is $350,000 to $400,000 per bed, consistent with University of Ghana Medical Centre actual costs of $352,000 per bed.

| Market Position | Anchor position in underserved region of 2.9 million residents |

| Teaching Hospital Status | University affiliation available on same site |

| Medical Tourism | Infrastructure to capture patients currently travelling to Accra or abroad |

| Capital Requirement | None—facility provided through lease structure |

The Queen Mamohato Memorial Hospital in Lesotho demonstrates the public-private partnership model for health infrastructure in low-income African settings.

| Structure | 18-year contract, Netcare-led consortium |

| Scale | 425 beds, approximately $100 million construction |

| Commissioning | October 2011 |

Results achieved:

| Extremely low birth weight infant survival | 70% (virtually zero before PPP) |

| Daily patient volume | 30% increase |

| Cost efficiency per patient | 22% improvement |

| Accreditation | Full COHSASA accreditation achieved |

The International Finance Corporation provided advisory services for the Lesotho transaction and continues to support health PPP development in low-income countries.

Healthcare systems meeting the following criteria:

| Africa Experience | Operations or expansion interest in Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Institutional Credit | Balance sheet strength to support lease or operating agreement |

| Teaching Hospital Experience | Medical education programme capability |

| Medical Tourism Capability | Experience serving patients from outside immediate catchment |

Examples include Aga Khan Health Services, Netcare, IHH Healthcare, and similar organisations with demonstrated capability in comparable settings.

The campus will comprise 68,200 square metres with emphasis on STEM and STEAM disciplines.

| Component | Area (m²) | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Buildings | 13,300 | $27.5 million |

| Student Housing | 11,400 | $23.6 million |

| Support Facilities | 9,300 | $19.2 million |

| Athletic Facilities | 27,000 | $55.8 million |

| Infrastructure | 7,200 | $14.9 million |

| Total | 68,200 | $141 million |

The cost basis is $2,068 per square metre ($192 per square foot), consistent with Bank of Ghana construction benchmarks as verified by Sovereign AEC.

The university partner will receive a purpose-built campus without the requirement to fund construction.

| Campus | 68,200 m² facility constructed to specifications |

| Teaching Hospital | Affiliation available with adjacent 300-bed tertiary facility |

| Scientific Backbone | National meteorological, hydrological, and agricultural data infrastructure role |

| Grant Eligibility | $55-280 million across meteorological, hydrological, agricultural, health, and education programmes |

| Faculty Pipeline | 30 PhD-level academics available for deployment |

Ghana law requires newly established private institutions to affiliate with a chartered public university before obtaining independent presidential charter. Twenty-one institutions currently maintain affiliation with University of Ghana alone.

The affiliate structure satisfies this requirement while enabling operational and financial independence for the international partner.

| Phase 1 | Establish affiliate entity under Ghana law |

| Phase 2 | Obtain affiliation agreement with chartered public university |

| Phase 3 | Operate under affiliate status while building track record |

| Phase 4 | Apply for independent presidential charter |

The timeline from affiliate establishment to independent charter typically spans five to ten years, depending on programme scope and institutional performance.

International universities meeting the following criteria:

| Africa Interest | Existing operations or stated expansion interest |

| Institutional Credit | Balance sheet strength to guarantee affiliate lease obligations |

| Programme Capacity | STEM and STEAM programme expertise |

| Medical Education | Interest in teaching hospital affiliation |

The stadium will accommodate 25,000 seats with covered design. This would represent West Africa's first covered stadium.

| Capacity | 25,000 seats |

| Coverage | Fully covered (climate control, rain protection) |

| Compliance | FIFA standards for international matches |

| Multipurpose | Football, concerts, events, conferences |

| Estimated Cost | Approximately $100 million |

West Africa currently has no covered stadium. The region's climate creates demand for weather-protected venues capable of hosting events year-round.

Ghana's national football team, the Black Stars, has faced venue certification challenges. The Confederation of African Football has restricted approval for certain existing venues. A compliant, covered facility addresses this gap.

| Regional Gap | No covered stadium in West Africa |

| National Need | FIFA-compliant venue for international matches |

| Event Capacity | Concerts, conferences, religious gatherings, exhibitions |

The stadium anchors the entertainment district. Event attendance generates demand for adjacent hotels, restaurants, and retail.

| Match Days | 25,000 attendees requiring food, beverage, parking, some requiring lodging |

| Concert Events | Regional draw for major performances |

| Conferences | Large-capacity venue for business and government events |

| Religious Gatherings | Covered venue for assemblies |

A stadium in isolation captures limited revenue from events. A stadium surrounded by hotels, restaurants, and entertainment captures spending throughout the visitor experience.

The stadium follows Phase 1 anchor facilities. Development sequence:

| Phase 1 | University and hospital establish anchor presence and demand base |

| Phase 2 | Stadium and entertainment district leverage anchor traffic |

| Rationale | Anchor facilities demonstrate viability; stadium financing follows proven demand |

The entertainment district will comprise 35 acres situated adjacent to the stadium, designed for walkability with all amenities accessible within a ten-minute walk.

Central Park, comprising 5 to 10 acres, will anchor the district with landscaped green space.

| Scale | 5-10 acres landscaped green space |

| Amphitheater | 2,000-seat performance venue |

| Purpose | Gathering space for residents, patients, students, visitors |

Urban planning research consistently demonstrates that people require gathering places and green areas. Parks improve quality of life, support mental health, and create community focal points.

Multiple hotel properties will serve diverse demand segments.

| Demand Source | Accommodation Need |

|---|---|

| Medical tourism patients | Extended stay during treatment and recovery |

| Patient families | Accommodation during hospital visits |

| University families | Lodging during campus visits, graduation, events |

| Stadium attendees | Overnight accommodation for regional visitors |

| Conference delegates | Business accommodation for events |

| Construction workforce | Temporary housing during development phases |

Multiple price points will be accommodated, from budget to premium categories. The diversity of demand drivers reduces occupancy risk from any single source.

The entertainment district will include dining and retail serving the daily population and event visitors.

| Daily Population | Hospital staff, university employees, students, residents |

| Event Traffic | Stadium attendees, conference delegates, visitors |

| Medical Support | Services for patients and families during hospital stays |

Retail and dining establishments create employment and keep spending circulating within the district rather than flowing elsewhere.

The district will be designed for human scale rather than vehicular scale.

| Walkability | All amenities within ten-minute walk |

| Scale | Intimate, pedestrian-oriented rather than sprawling |

| Green Space | Central Park as community focal point |

| Mixed Use | Residential, commercial, entertainment integrated |

Successful entertainment districts worldwide share these characteristics. The design creates environments where people want to spend time rather than merely pass through.

The development will include housing serving multiple population segments, operating on a leasehold model that preserves traditional land ownership while enabling development.

| Category | Population Served | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Student Housing | University enrollment | Dormitory and apartment configurations |

| Faculty and Staff Residences | University and hospital professionals | Apartment and single-family options |

| Workforce Housing | District employees, construction workers | Affordable rental units |

| Family Communities | Long-term residents | Leasehold homes with purchase option |

Housing will operate on a leasehold model rather than freehold ownership.

| Land Ownership | Remains with traditional authority |

| Lease Term | 99-year renewable leases available |

| Improvements | May be bought and sold during lease term |

| At Lease End | Improvements transfer with land to traditional authority |

This structure respects customary land tenure while enabling housing development. Residents gain long-term security. Traditional authority retains ultimate ownership.

The development will prioritise local employment and housing access.

| Construction Employment | Priority hiring from Akyem Apedwa and surrounding communities |

| Operational Positions | Training and placement programmes for local residents |

| Displaced Persons | Employment and housing access for those affected by development |

| Workforce Housing | Affordable units ensuring workers can live near employment |

Development that displaces communities without providing alternatives creates harm. This structure ensures that those affected by development also benefit from it.

| Phase 1 | Student housing integrated with university campus |

| Phase 2 | Faculty and staff residences as operations commence |

| Phase 3 | Workforce housing as district employment grows |

| Ongoing | Family communities as demand demonstrates viability |

Housing development follows demonstrated demand. Each phase is separately financeable based on anchor facility success and occupancy commitments.

Additional components will develop as the district matures and demand demonstrates viability.

District-wide infrastructure will serve all components and provide foundation for future expansion.

| Roads | Internal circulation, connection to regional network |

| Power | Grid connection, backup generation, potential solar integration |

| Water | Supply, treatment, distribution |

| Sewerage | Collection and treatment systems |

| Fibre Connectivity | High-speed data infrastructure throughout district |

| Stormwater | Drainage and management systems |

Infrastructure costs are distributed across all components. Shared infrastructure reduces per-facility costs compared to standalone development.

The construction approach will emphasise locally-sourced materials where feasible.

| Brick | Fired clay from local deposits |

| Stone | Quarried granite from regional sources |

| Timber | Ghana-milled hardwood |

| Labour | Priority hiring from local communities |

Economic rationale: A project of $280 million using imported materials sends capital out of Ghana. The same project using Ghana-made materials keeps capital circulating within the local economy. Construction workers earning wages become customers for businesses in the entertainment district.

Cost consideration: Local brick construction typically costs 15 to 25 percent less than imported curtain wall systems while employing more local labour per dollar spent.

Ghana possesses a heritage of brick and stone construction. Holy Trinity Cathedral in Accra, Wesley College, and numerous other institutions demonstrate durable, climate-appropriate construction using local materials.

The university campus may incorporate agricultural research and extension services.

| Research | Agricultural science programmes, soil research, crop improvement |

| Extension | Farmer training, technology transfer, advisory services |

| Data Infrastructure | Weather monitoring, soil databases, agricultural information systems |

| Food Security | Local food production, supply chain improvement |

Agricultural components align with grant funding opportunities and address food security challenges affecting the region.

The university may serve as Ghana's scientific backbone, operating data infrastructure that serves national needs.

| Meteorological | Weather observation network, climate monitoring |

| Hydrological | Flood forecasting, groundwater monitoring, water resource data |

| Agricultural | Crop monitoring, soil mapping, farm advisory systems |

| Health Informatics | Disease surveillance, health data systems |

This infrastructure role attracts substantial grant funding while providing services that benefit Ghana beyond the university itself. Details appear in the Grants section.

3. Structure

The business structure, land arrangements, and organizational framework that enables the Ghana Medical City development.

The development employs institutional tenant credit rather than sovereign credit to support construction financing.

International capital markets apply risk premiums to emerging market sovereign obligations. These premiums reflect assessments by third-party credit rating agencies of payment reliability over multi-decade horizons.

The structure proposed here does not rely on government appropriations. Institutional tenants—the university and healthcare operator—provide the credit foundation. Their lease commitments, backed by their own balance sheets and revenue streams, satisfy construction lender requirements.

| University Credit Source | Parent institution guarantee of affiliate lease obligations |

| Hospital Credit Source | Healthcare operator corporate credit backing operating agreement |

| Ghana Contribution | Land, regulatory pathway, expression of support |

| Ghana Financial Obligation | None |

Construction financing carries costs reflecting development risk. Stabilised assets with creditworthy tenants trade at lower capitalisation rates.

| Stage | Capitalisation Rate | Value of $11.2M Annual Income |

|---|---|---|

| Construction (development risk) | 8% | $140 million |

| Stabilised (institutional tenant) | 6% | $187 million |

| Value Creation | $47 million |

The institutional credit compresses the capitalisation rate. The resulting spread represents development profit that compensates for execution risk.

A creditworthy tenant transforms speculative construction into an investment-grade asset.

| Long-term Lease | Provides predictable income stream over decades |

| Institutional Credit | Removes tenant default risk from investor concern |

| Stabilised Asset | Attracts pension funds, insurance companies, REITs seeking stable returns |

The developer exits with profit from cap rate compression. The tenant receives a facility without capital outlay. Investors receive stable income. Ghana receives infrastructure without fiscal burden.

| Step 1 | Institutional tenant signs long-term lease commitment |

| Step 2 | Construction lender provides financing against lease commitment |

| Step 3 | Developer builds facility using construction financing |

| Step 4 | Tenant occupies facility, begins lease payments |

| Step 5 | Developer sells stabilised asset to institutional investor at compressed cap rate |

| Step 6 | Construction loan repaid, development profit realised |

The land comprises 553 acres demarcated in Akyem Apedwa, Eastern Region, Ghana.

| Location | Akyem Apedwa, Eastern Region |

| Acreage | 553 acres demarcated |

| Traditional Authority | Chief of Apedwa and elders have demarcated land for project |

| Intermediary | Dr. David Ofori, Ahenanahene of Akyem Apedwa |

| Documentation | Ready, Willing, and Able letter on file |

Ghana land tenure operates through customary systems in which traditional authorities hold land in trust for their communities.

| Step | Description | Status |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial Engagement | Introduction to traditional authority, expression of interest | Complete |

| 2. Land Identification | Traditional authority demarcates suitable land | Complete |

| 3. Ready, Willing, and Able Letter | Traditional authority confirms availability | Complete |

| 4. Customary Affirmation | Formal payment to Paramount Chief initiating process | Pending |

| 5. Survey and Documentation | Professional survey, boundary documentation | Pending |

| 6. Lease Agreement | Formal lease terms negotiated and executed | Pending |

| 7. Lands Commission Registration | Registration with Ghana Lands Commission | Pending |

The Akyem Apedwa traditional authority operates within the broader Akyem traditional structure.

| Paramount Chief | Highest traditional authority for the area |

| Chief of Apedwa | Local traditional authority for Akyem Apedwa |

| Elders and Council | Advisory body to the Chief |

| Ahenanahene | Dr. David Ofori serves in this traditional role |

Engagement proceeds through proper channels with respect for traditional hierarchy and customary protocol.

| Term | Long-term lease (to be negotiated) |

| Land Ownership | Remains with traditional authority |

| Development Rights | Granted to lessee for term of lease |

| Improvements at End of Term | Transfer to Ghana |

| Customary Fees | Appropriate payments through proper channels |

The lease structure preserves traditional ownership while enabling development. Land is not sold. Traditional authority maintains ultimate ownership; development rights are leased for a defined term.

Development proceeds in phases, with each phase building on the success of preceding work.

| Milestone | Description |

|---|---|

| Land Control Letter | Formal land commitment from traditional authority |

| University Letter of Interest | Expression of interest from university partner |

| Healthcare Operator LOI | Expression of interest from healthcare operator |

| Construction Partner Confirmation | Confirmation of participation from construction partner |

| Pre-development Funding | Capital to complete investor-ready package |

These four commitment documents—land, university, hospital, construction—substantially de-risk the development and enable construction financing.

| Activity | Duration |

|---|---|

| Pre-development and Partnership Finalisation | 6-12 months |

| Design Development | 6-9 months |

| Construction Financing Close | 3-6 months |

| University Campus Construction | 24-30 months |

| Hospital Construction | 24-36 months |

| Commissioning and Operations Commencement | 3-6 months |

| Total Phase 1 | 4-5 years from partnership finalisation |

| Phase | Components | Trigger |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 2 | Stadium, Entertainment District | Anchor facilities operational, demand demonstrated |

| Phase 3 | Housing expansion, additional commercial | Phase 2 success, continued demand |

| Ongoing | District maturation, additional facilities | Market conditions, operator interest |

Each phase is separately financeable. Success of preceding phases reduces risk and improves financing terms for subsequent phases.

| Land | Customary affirmation and formal documentation |

| University Partner | Identification and commitment from institutional partner |

| Healthcare Operator | Identification and commitment from hospital operator |

| Pre-development Funding | Capital to complete investor-ready documentation |

These items may proceed in parallel. Completion of all four enables construction financing and project execution.

The full district represents an investment of approximately $1.1 billion across all phases. Phase 1 comprises approximately $280-310 million.

| Component | Estimated Cost | Credit Source |

|---|---|---|

| University Campus (68,200 m²) | $141 million | University institutional credit |

| Teaching Hospital (300 beds) | $120-140 million | Healthcare operator credit |

| Shared Infrastructure | $20-30 million | Allocated across anchor facilities |

| Phase 1 Total | $280-310 million |

Estimated costs are based on documented benchmarks.

| Component | Benchmark | Source |

|---|---|---|

| University construction | $2,068/m² ($192/sf) | Bank of Ghana benchmarks, verified by Sovereign AEC |

| Hospital construction | $350,000-400,000/bed | University of Ghana Medical Centre actual costs |

Final costs will be determined through detailed design and construction bidding. These estimates provide planning-level accuracy for development feasibility.

| Component | Estimated Range |

|---|---|

| University Campus | $141 million |

| Teaching Hospital | $120-140 million |

| Covered Stadium (25,000 seats) | ~$100 million |

| Entertainment District | To be determined |

| Housing Districts | To be determined |

| Infrastructure | To be determined |

| Estimated Total | ~$1.1 billion |

Future phase costs will be refined as anchor facilities demonstrate viability and detailed programming is completed.

| Source | Application |

|---|---|

| Construction Financing | Secured against institutional tenant lease commitments |

| Pre-development Funding | Preparation of investor-ready package, partnership documentation |

| Grant Funding | $55-280 million potential across eligible programmes (optional upside) |

| Ghana Government | None required |

The development team assembles capabilities across land, construction, development, and academic domains.

Development entity for Ghana Medical City.

| Role | Development lead, partnership coordination |

| Structure | NSG 51% / TMB 49% |

| Principals | Jey Smith, Michael Hoffman |

| Location | Fairhope, Alabama, United States |

| Focus | Systems integration, affordable housing development, grant funding strategy |

| Role | Financial structuring, grant opportunities, development coordination |

| Principal | Michael Hoffman, CEO and Founder |

| Experience | 32 years real estate development, 9 US patents, 18+ million square feet managed |

| Dr. David Ofori | Ahenanahene of Akyem Apedwa; traditional authority relationships, local presence |

| Role | Traditional authority engagement, customary process facilitation |

| Isra Holding | Turkish construction firm |

| Africa Portfolio | $85 billion in completed and ongoing projects |

| Experience | Regional experience across Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Role | Design-build construction services |

| Sovereign AEC | Architecture, engineering, and construction consulting |

| Role | Facility programming, cost verification, design coordination |

| Deliverables | Programming documents, preliminary cost estimates |

| Faculty Pipeline | 30 PhD-level academics available for deployment |

| Coordination | Dr. Donovan Outten and academic network |

| Disciplines | STEM and STEAM fields aligned with university programming |

The development addresses fundamental gaps in healthcare access, educational capacity, and economic opportunity.

The Eastern Region's 2.9 million residents currently lack access to a tertiary teaching hospital within their region.

| Current State | No tertiary teaching hospital in Eastern Region |

| Travel Required | Hours to reach Korle-Bu (Accra) or Komfo Anokye (Kumasi) |

| Impact | For trauma, stroke, cardiac events, and complicated births, travel time affects outcomes |

| After Development | 300-bed tertiary teaching hospital serving the region |

When a person suffers a stroke, every minute without treatment increases the likelihood of permanent disability or death. When a birth becomes complicated, access to surgical intervention determines whether mother and child survive. Distance matters. This hospital addresses that distance.

Ghana's tertiary enrollment rate of 21.99 percent falls nearly 18 percentage points below the global average of 40.35 percent.

| Current Gap | 18.36 percentage points below global average |

| Practical Impact | Qualified students turned away each year due to capacity constraints |

| Outflow | 20,300 students studying abroad (2021) |

| After Development | 68,200 m² university campus adding capacity for thousands of students |

Each student denied a university place represents unrealised potential. Each student sent abroad to study represents capital and talent flowing out of Ghana. Expanded capacity keeps students and their tuition payments within the country.

| Phase | Employment Created |

|---|---|

| Construction (Phase 1) | Thousands of construction positions over 24-36 months |

| Hospital Operations | Physicians, nurses, technicians, administrators, support staff |

| University Operations | Faculty, administrators, maintenance, security, food service |

| Entertainment District | Hotel, restaurant, retail, and service positions |

| Indirect Employment | Suppliers, vendors, service providers throughout the region |

Construction employment using local materials and local labour keeps wages circulating within the local economy. Workers earning wages become customers for local businesses.

At the conclusion of the lease term, infrastructure transfers to Ghana.

| During Lease Term | Institutional partners operate facilities, service lease obligations |

| At Lease End | Improvements transfer to Ghana ownership |

| Options | Ghana may negotiate renewal, transition to new operator, or assume direct operation |

Ghana receives functioning infrastructure without incurring construction debt. The facilities serve Ghanaian residents throughout the lease term, then become national assets.

| Government Funding Required | None |

| Sovereign Guarantee Required | None |

| Impact on National Debt | None |

| Tax Revenue Generated | Corporate taxes, payroll taxes, consumption taxes from district activity |

The development creates tax revenue rather than consuming fiscal resources. Infrastructure is delivered without adding to sovereign debt obligations.

4. Grants & Research Funding

International grant opportunities supporting research, data collection, and capacity building across the development's educational and healthcare missions.

Grant funding represents optional upside. The core financing structure does not depend on grant success. However, the potential magnitude warrants documentation and pursuit.

| Category | Funding Range | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Meteorological Infrastructure | $5-20 million | WMO SOFF, Green Climate Fund, CREWS |

| Hydrological Monitoring | $10-50 million | GCF, GEF, World Bank GFDRR |

| Agricultural Technology | $10-50 million | IFAD, Gates Foundation, AfDB, EU |

| Health Infrastructure | $20-100 million | Global Fund, World Bank IDA, AfDB |

| Data Centre Infrastructure | $5-30 million | Digital development programmes, Power Africa |

| University and Research | $5-30 million | NIH Fogarty, Wellcome Trust, African Academy of Sciences |

| Total Potential Range | $55-280 million |

The range reflects programme variability and application success rates. Not all categories would be pursued simultaneously. A university partner with established grant-writing capacity and international credibility significantly improves success probability across all categories.

Grant applications require institutional credibility, documented need, and alignment with funder priorities. The university partner provides the institutional foundation that strengthens applications across all categories.

| Institutional Standing | Established universities have relationships with major funders |

| Grant-Writing Capacity | Experienced staff who understand funder requirements |

| Track Record | History of successful grant execution improves future applications |

| Research Infrastructure | Laboratories, data systems, and protocols that funders expect |

These grant programmes are organised by sector and objective rather than by country. The same funding sources support projects in Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, and other eligible countries.

Eligibility depends on programme alignment, institutional capacity, and documented need—not on country-specific allocations. Ghana's status as an ODA-eligible country makes most programmes accessible.

Teaching hospitals and health workforce development attract funding from global health initiatives and development finance institutions. Digital infrastructure attracts funding from connectivity and digital transformation programmes.

| Source | Programme | Funding Range |

|---|---|---|

| Global Fund | Health systems strengthening | $10-50 million |

| World Bank IDA | Health infrastructure | $20-100 million |

| African Development Bank | Health sector development | $10-50 million |

| USAID | Health workforce, facilities | $5-30 million |

| DFID/FCDO | Health systems | $5-20 million |

| GIZ | Health infrastructure | $3-15 million |

| Wellcome Trust | Health research, capacity building | $500,000-$10 million |

Africa's data centre capacity is growing but remains undersupplied relative to demand. Cloud services, AI applications, and digital transformation all require physical data centre infrastructure.

| Source | Programme | Funding Range |

|---|---|---|

| Power Africa | Energy infrastructure for digital | $5-20 million |

| World Bank Digital Development | Connectivity and digital infrastructure | $10-50 million |

| African Development Bank | ICT infrastructure | $5-30 million |

| IFC InfraVentures | Early-stage infrastructure | $5-15 million |

| European Investment Bank | Digital infrastructure | $10-50 million |

| Google/Microsoft Africa initiatives | Digital skills and infrastructure | $1-10 million |

Data centres require reliable power—redundant grid connection plus backup generation. Funding for power infrastructure often combines with digital infrastructure programmes.

| Source | Programme | Funding Range |

|---|---|---|

| Power Africa | Generation and distribution | $10-50 million |

| Green Climate Fund | Renewable energy | $10-100 million |

| African Development Bank | Energy infrastructure | $20-100 million |

| Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa | Project preparation | $1-5 million |

Smallholder farmers produce crops that could command premium prices in international markets, but they lack documentation to prove origin, quality, and compliance with buyer requirements.

The European Union's Deforestation Regulation, effective December 2025, requires GPS-level traceability for cocoa, coffee, palm oil, soy, cattle, rubber, and timber. Products without documented origin will be excluded from EU markets.

Geolocation requirements:

| Plots under 4 hectares | Single GPS point (latitude and longitude, six decimal digits minimum) |

| Plots 4 hectares or larger | Complete polygon describing the perimeter |

Ghana exports substantial cocoa volume to European markets. Farmers who cannot provide EUDR-compliant documentation risk losing market access entirely.

Documented price premiums exist for traceable, certified, and quality-verified agricultural products.

| Product Type | Commodity Price | Certified/Traceable Price | Premium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cocoa (conventional) | $1,560/tonne | $2,650/tonne (Fairtrade) | +70% |

| Cocoa (organic + traceable) | $1,560/tonne | $4,100/tonne | +163% |

| Coffee (certified) | Variable | 15-30% premium | +15-30% |

| Palm Oil (RSPO certified) | Variable | 5-10% premium | +5-10% |

A typical smallholder cocoa farmer producing 1,000 kg annually could increase income from $1,560 to $2,650-4,100 with certification and traceability—an increase of $1,090 to $2,536 per farmer per year.

| Source | Programme | Funding Range |

|---|---|---|

| IFAD (UN) | Smallholder agriculture, rural development | $10-50 million |

| Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation | Agricultural development in Africa | $5-30 million |

| African Development Bank | Food security, agricultural productivity | $5-20 million |

| World Bank | Agricultural modernisation | $10-100 million |

| European Union | EUDR implementation support | $5-15 million |

| Mastercard Foundation | Youth employment, agricultural livelihoods | $5-25 million |

Weather observation networks remain severely underdeveloped across West Africa. The World Meteorological Organization standard calls for one station every 100 miles. Current coverage falls far below this threshold.

In 2021, the 193 member countries of the World Meteorological Organization adopted technical regulations establishing GBON—a global standard for minimum weather observation requirements.

GBON requirements include:

| Surface stations | Specified horizontal resolution requirements |

| Upper-air soundings | Specified frequency requirements |

| Data sharing | Mandatory international data sharing |

| Quality standards | Defined data quality requirements |

| Transmission | Timely transmission to global weather centres |

The economic case: A World Bank and WMO study estimated that closing observation gaps and improving forecasts could unlock $160 billion in economic benefits globally. Every dollar invested returns over 25:1 in avoided losses and economic gains.

SOFF is a United Nations fund created in 2022 by WMO, UNDP, and UNEP to close weather observation gaps in countries that lack resources to build and maintain compliant networks.

Eligibility: Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States receive priority. Other Official Development Assistance-eligible countries can access technical assistance.

Three phases of support:

| Readiness | Technical assistance to analyse gaps and develop National Contribution Plans |

| Investment | Grants for equipment purchase, installation, training, and capacity building |

| Compliance | Results-based funding for ongoing operations and maintenance |

Funding levels: Individual country awards range from $3-10 million. SOFF has approved over $27 million for Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Solomon Islands. Rwanda received $3.1 million. Total facility target is $400 million over five years.

| Source | Programme | Funding Range |

|---|---|---|

| WMO SOFF | GBON compliance | $5-15 million |

| Green Climate Fund | Climate information services | $10-20 million |

| CREWS Initiative | Climate Risk Early Warning | $3-8 million |

| World Bank | Hydromet modernisation | $5-10 million |

- World Meteorological Organization. "Systematic Observations Financing Facility." alliancehydromet.org/soff (Accessed December 2025)

- World Meteorological Organization. "Global Basic Observing Network (GBON)." community.wmo.int (Accessed December 2025)

- Green Climate Fund. Official website. greenclimate.fund (Accessed December 2025)

Flood early warning systems, groundwater management, and water resource planning attract funding from climate adaptation programmes.

Lead time—the interval between warning and flood arrival—determines what protective response is possible.

| Lead Time | Response Possible |

|---|---|

| 1-2 hours | Immediate evacuation only |

| 6-12 hours | Move assets, livestock; prepare shelters |

| 1-3 days | Preposition supplies; deploy emergency personnel; staged evacuation |

| 5-10 days | Harvest crops; reinforce infrastructure; coordinate regional response |

The United Nations estimates that 24-hour advance warning of a storm reduces deaths by 30 percent. Earlier warning with accurate information saves more lives and enables better resource allocation by emergency managers.

Satellite-based and global modelling systems complement ground-based monitoring.

| GloFAS | Global Flood Awareness System operated by European Commission's Copernicus Emergency Management Service. Provides daily flood forecasts up to 30 days ahead. Lead times of 5-10 days achievable for large African rivers. |

| Google Flood Hub | AI-based flood forecasting providing 7-day forecasts. Extended reliable forecasts from zero to five days in data-scarce regions. Forecasts in Africa now comparable to European accuracy despite less ground data. |

| Source | Programme | Funding Range |

|---|---|---|

| Green Climate Fund | Climate adaptation infrastructure | $10-50 million |

| Global Environment Facility | Water resources management | $3-15 million |

| World Bank GFDRR | Disaster risk management | $10-100 million |

| African Development Bank | Water security infrastructure | $5-20 million |

| WMO WHYCOS | Regional hydrological monitoring | $3-10 million |

| CREWS Initiative | Early warning systems in LDCs | $3-8 million |

Academic institutions with African presence attract education development and research funding across multiple programme areas.

| Source | Programme | Funding Range |

|---|---|---|

| National Institutes of Health (Fogarty) | Natural products, research training | $500,000-$5 million |

| Wellcome Trust | Research capacity building Africa | $500,000-$10 million |

| Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation | Health and agricultural research | $1-20 million |

| African Academy of Sciences | Research grants, capacity building | $50,000-$500,000 |

| Royal Society | Research partnerships | £50,000-£500,000 |

| Carnegie Corporation | Higher education in Africa | $500,000-$5 million |

| Source | Programme | Funding Range |

|---|---|---|

| World Bank | Higher education development | $10-100 million |

| African Development Bank | Skills and education | $5-30 million |

| Mastercard Foundation | Scholars and institutional support | $5-50 million |

| USAID | Higher education partnerships | $3-20 million |

Grant applications benefit from strategic sequencing.

| Phase | Focus | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-development | Climate/meteorological, agricultural | Fastest approval cycles, builds track record |

| Construction | Health infrastructure, digital development | Larger amounts, longer timelines |

| Operations | Research, education, capacity building | Ongoing programme support |

Success factors:

| Documented need | Eastern Region's lack of tertiary hospital, national gaps in weather observation, agricultural traceability |

| Institutional anchor | Credentialed university partner with international standing |

| Integration | Multi-sector proposals demonstrating systemic impact |

| Government support | Letters of support strengthen applications without requiring funding |

5. Key Questions

Answers to frequently asked questions from investors, government officials, and development partners considering involvement with Ghana Medical City.

This section addresses questions about why the development is structured as proposed rather than through alternative approaches.

Ghana's Eastern Region hospital project, valued at €70 million, experienced interruption when fiscal constraints affected the payment schedule. The contractor departed. The facility remains incomplete.

This experience illustrates a broader pattern. International capital markets apply risk premiums to emerging market sovereign obligations. These premiums reflect assessment by third-party credit rating agencies of payment reliability over multi-decade horizons.

The structure proposed here does not rely on government appropriations. Institutional tenants—the university and healthcare operator—provide the credit foundation. Their lease commitments, backed by their own balance sheets and revenue streams, satisfy construction lender requirements.

| What Government Provides | What Government Does Not Provide |

|---|---|

| Land allocation through traditional authority facilitation | Construction funding |

| Regulatory pathway support | Operating subsidies |

| Expression of public commitment | Lease payment guarantees |

The government gains infrastructure without fiscal burden.

A Ghana-registered entity without operating history possesses limited credit standing. Construction lenders require assurance of lease payment over terms spanning decades.

International institutions with established balance sheets and operating track records can provide this assurance. Their institutional credit renders the financing bankable at costs reflecting their credit quality rather than Ghana sovereign risk premiums.

| Local Entity Credit | Limited; insufficient for construction financing |

| Ghana Sovereign Credit | Subject to risk premiums that increase financing costs |

| International Institutional Credit | Established; satisfies lender requirements at lower cost |

The institutional credit transforms speculative construction into an investment-grade asset.

Minimum viable scale determines project scope:

| Hospital | A 100-bed district hospital serves local needs but cannot support medical tourism, teaching programmes, or tertiary specialty services. A 300-bed tertiary teaching hospital reaches the threshold for these functions. |

| University | A campus below critical mass cannot attract international faculty, sustain research programmes, or achieve the institutional presence that justifies lease commitment. The 68,200 m² programming represents minimum scale for comprehensive university presence. |

| Stadium | A 10,000-seat venue cannot host FIFA international matches or major concerts. A 25,000-seat covered stadium reaches viable scale for both functions. |

The components are sized to their minimum viable scale, not to arbitrary targets.

The land comprises 553 acres demarcated in Akyem Apedwa, Eastern Region.

| Traditional Authority | Chief and elders have demarcated land for lease; intermediary engaged |

| Regional Need | Eastern Region serves 2.9 million with no tertiary hospital |

| Land Pathway | Customary process understood; Ready, Willing, and Able letter on file |

| Acreage | 553 acres sufficient for full district development |

This is not speculative land identification. Traditional authorities have been engaged and are receptive. The pathway to formal documentation is understood.

No single entity possesses all required capabilities. The team structure assembles necessary expertise:

| Function | Capability |

|---|---|

| Land Pathway | Dr. David Ofori—traditional authority relationships, local presence |

| Construction | Isra Holding—Turkish firm, $85 billion Africa portfolio |

| Development Strategy | North Star Group—financial structuring, grant opportunities |

| Architecture and Programming | Sovereign AEC—facility programming, cost verification |

| Academic Leadership | PhD faculty pipeline—30 academics available for deployment |

The development lead coordinates these capabilities toward a common objective.

The gaps are documented. The pathway is clear. The team is assembled.

| Healthcare Gap | Eastern Region has no tertiary hospital; €70M government project remains incomplete |

| Education Gap | Ghana tertiary enrollment 18 percentage points below global average |

| Land Pathway | Demarcated, traditional authority engaged, documentation pathway clear |

| Team | Each function has identified capability ready to execute |

The question is not whether Ghana needs this infrastructure. The question is whether a credible pathway exists to deliver it.

This structure provides that pathway.

This section addresses questions regarding the land pathway and traditional authority engagement.

The Chief of Apedwa and elders have demarcated 553 acres for lease to the project team.

| Location | Akyem Apedwa, Eastern Region, Ghana |

| Acreage | 553 acres demarcated |

| Traditional Authority | Engaged and receptive |

| Intermediary | Dr. David Ofori, Ahenanahene of Akyem Apedwa |

| Documentation | Ready, Willing, and Able letter on file |

Ghana customary land tenure follows established procedures that respect traditional authority.

| Step 1 | Expression of interest to traditional authority |

| Step 2 | Land demarcation by Chief and elders |

| Step 3 | Customary affirmation payment to Paramount Chief |

| Step 4 | Formal lease documentation |

| Step 5 | Registration with Lands Commission |

Steps 1 and 2 are complete. Step 3 initiates formal documentation. This is not speculative land acquisition—traditional authorities have been engaged and are receptive.

The traditional authority and people of Akyem Apedwa receive substantial benefits while retaining underlying land ownership.

| Customary Fees | Appropriate payments through proper channels to traditional authority |

| Employment Priority | Construction and operational positions prioritised for local residents |

| Healthcare Access | Tertiary hospital within the community—no travel to Accra or Kumasi |

| Education Access | University facilities serving the region |

| Economic Activity | Wages and purchasing circulating in local economy |

| Infrastructure | Roads, power, water, fibre serving the district and surrounding area |

| Land Retention | Term lease preserves traditional ownership; improvements transfer at conclusion |

The construction approach emphasises local materials and local employment.

| Materials | Brick, stone, timber sourced from Ghana where feasible |

| Labour | Priority hiring from Akyem Apedwa and surrounding communities |

| Training | Skills development for local workforce |

| Displaced Persons | Employment and housing available for those affected by development |

A project of this scale using imported materials sends capital out of Ghana. The same project using Ghana-made materials keeps capital circulating within the local economy. Workers earning wages become customers for businesses throughout the district.

Development that displaces communities without providing alternatives creates harm. This structure ensures that those affected by development also benefit from it.

The term lease provides development rights while preserving traditional ownership.

| Underlying Ownership | Remains with traditional authority throughout |

| Lease Term | Long-term (typically 50-99 years, subject to negotiation) |

| Lease Payments | Annual ground rent to traditional authority |

| At Lease End | Improvements transfer to traditional authority with land |

This is infrastructure development, not land alienation. The traditional authority provides access for a term. At conclusion, Akyem Apedwa receives world-class healthcare, education, and entertainment facilities built on their land.

The development team seeks formal commitment from traditional authority to proceed with documentation.

| Immediate | Confirmation of willingness to proceed with lease documentation |

| Following | Customary affirmation payment initiates formal process |

| Documentation | Formal lease agreement negotiated with legal counsel |

| Registration | Lands Commission registration upon execution |

The development team has demonstrated seriousness through extensive preparation. The traditional authority's formal commitment enables advancement to the next phase.

This section addresses questions that prospective healthcare operators typically raise when evaluating hospital development opportunities in emerging markets.

International capital markets apply risk premiums to emerging market sovereign obligations. These premiums affect financing costs and capitalisation rate expectations.

The structure addresses this through institutional tenant credit:

| Traditional Structure | This Structure |

|---|---|

| Government commits to payments | Healthcare operator commits to lease obligations |

| Financing costs reflect sovereign risk premium | Financing costs reflect operator credit quality |

| Capitalisation rate limited by sovereign rating | Capitalisation rate reflects institutional tenant quality |

The healthcare operator's corporate credit—not government appropriations—provides the foundation that capital markets require.

The Eastern Region of Ghana serves a population of 2.9 million residents. At present, the region has no tertiary teaching hospital.

| Population Served | 2.9 million (2021 Census) |

| Current Tertiary Access | None within region; travel to Accra or Kumasi required |

| Regional Hospital | Koforidua provides secondary care; not tertiary teaching level |

| Government Project Status | €70 million hospital experienced interruption; facility incomplete |

The need documented a decade ago persists. The gap in care persists. The outcomes resulting from delayed access to tertiary care persist.

The operator does not fund construction. The operator provides:

| Lease Commitment | Corporate credit that supports financing structure |

| Clinical Operations | Medical services, quality standards, patient care |

| Management Expertise | Facility operations, staffing, procurement, systems |

| Brand and Reputation | Patient confidence, referral networks, medical tourism draw |

| Anchor Position | First tertiary hospital in underserved region of 2.9 million |

| Teaching Hospital Status | University affiliation provides medical education integration |

| Purpose-Built Facility | 300-bed hospital constructed to operator specifications |

| Medical Tourism Infrastructure | Regional draw for specialty services currently unavailable locally |

| No Capital Outlay | Facility provided through lease structure, not ownership purchase |

| Patient Services | Inpatient, outpatient, emergency, and specialty care |

| Medical Tourism | Regional patients seeking services unavailable locally |

| Teaching Programmes | Medical education fees, residency programme funding |

| Research | Clinical trial revenues, grant-funded research |

| Ancillary Services | Laboratory, imaging, pharmacy, rehabilitation |

Multiple revenue streams reduce dependence on any single source. Teaching hospital status and medical tourism add revenue beyond standard patient services.

A letter of interest initiates the process. This non-binding expression of interest enables:

| Facility Programming | Development of specifications meeting operator requirements |

| University Integration | Engagement with university partner on teaching hospital structure |

| Operating Projections | Development of preliminary financial models |

| Regulatory Pathway | Documentation of licensing and accreditation requirements |

A formal operating agreement or lease commitment follows completion of due diligence, negotiation of terms, and satisfaction of corporate approval processes.

This section addresses questions that prospective university partners typically raise when evaluating international campus development opportunities.

Ghana law requires newly established private institutions to affiliate with a chartered public university before obtaining independent presidential charter. Twenty-one institutions currently maintain affiliation with University of Ghana alone.

The affiliate structure serves multiple functions:

| Regulatory Compliance | Satisfies Ghana accreditation pathway requirements |

| Financial Independence | Affiliate maintains own accounts and revenue management, separate from consolidated public treasury structures |

| Credit Foundation | Parent institution guarantee provides institutional credit that construction lenders require |

| Operational Flexibility | International partner retains control over academic programmes and operations |

The university does not fund construction. The university provides:

| Lease Commitment | Institutional credit that makes construction financing bankable |

| Academic Programming | Accredited degree programmes, faculty oversight, quality assurance |

| Research Capacity | Grant eligibility, scientific infrastructure, faculty expertise |

| Institutional Credibility | Reputation that attracts students, faculty, and funding |